How to go to Europe and receive an "escapee" status there

Despite the decrease of the number of terror acts and of the militants' activeness in Chechnya, Chechens do not cease their attempts to go to Europe and claim for the refugee status there. Some of them are trying to receive the refugee status because of persecutions at home, others go there hoping to earn money, and yet others want to obtain a highly qualified medical care for themselves and their relatives. A journalist of the "Caucasian Knot" has covered the whole way, traditionally followed by Chechen refugees, leaving Russia for Europe, aiming to receive refuge ("azul"), thus, undertaking the so-called "azultrip".

Azultrip in the Chechen way

Despite the reduction of the number of terror acts and of the militants' activeness in Chechnya, Chechens do not cease their attempts to go to Europe and claim for the refugee status there. They continue leaving the region, which is regarded by official authorities as one of the calmest and most prosperous.

Some of them are trying to receive the refugee status because of persecutions at home, others go there hoping to earn money, and yet others want to obtain a highly qualified medical care for themselves and their relatives.

Most of them have a desire to receive the refugee status, and educate their children for them to easier integrate into the European society. Not all of them manage to achieve the desired – many Chechens are deported from the countries of Europe either back to Russia, or to the initial point of entering the European Union. Those, who manage to stay in Europe, are often treated as second-class people, while the general distrust for the natives of Northern Caucasus, who are associated in mass consciousness with the Islamic radicalization and terrorism, adds them no popularity, and is a more and more frequent obstacle to obtaining the so desired refugee status. The recent terror acts committed in European countries – France and Belgium, for which natives from the Caucasus were indiscriminately blamed by "yellow" and right-wing mass media, are another confirmation of this rule.

A journalist of the "Caucasian Knot" has covered the whole way, traditionally followed by Chechen refugees, leaving Russia for Europe, aiming to receive refuge ("azul"), thus, undertaking the so-called "azultrip". 1

Having started from the Belarusian Railway Station in Moscow, our reporter reached the Belarusian city of Brest, and further – by electric train – to the Polish border checkpoint in the town of Terespol. Pausing a little at that very platform, which, when trains with refugees arrive there, is tightly surrounded by the Polish border guards, our reporter passed freely his visa control at the station. For many Chechens, this is the first point of entry to Europe, where they have to convince the border service officers to let them into Poland, or face deportation back to the territory of Belarus. Our reporter went to Warsaw, where he communicated with members of the local NGO "Salvation", which helps refugees, with the Chechens, who run their small businesses, and with Luiza Adaeva, the head Chechen cultural association "Sintar".

After reaching the capital of Germany, our reporter met Ekkehard Maas, the head of the German-Caucasian Society, who said that his society is regularly visited by dozens of Chechens with their problems. The data collected by the reporter during the trip are narrated in the article below, which describes how and why Chechens are leaving Chechnya and Russia.

How many of them leave and to what countries

The main overland route is to Poland via Belarus. Many view Poland only as the entry point, and tend to continue their travel further to the West, especially to Germany, and more seldom – to Austria, France, Belgium and Denmark.

According to the Office for Foreigners of Poland, from 2009 till May 2015, over 39,000 citizens of Russia, the majority of them – natives of Chechnya, applied for the refugee status in Poland. 2

The year 2013 was the record year by the number of applications for asylum submitted in Poland and Germany; over 12,800 and 15,500 citizens of Russia, 90% of them being residents of Chechnya, did it in that year, respectively. Thus, Russia was the leader among the countries whose citizens sought refuge in Poland and Germany (83.3% and 14.5% of the total number of asylum-seekers). 3

In that time, rumours were actively spread over Chechnya that Germany had allocated quotas for the reception of 40,000 Chechens; that the migrants would be provided with all the necessary things and items; and that the state would allocate at least 2000 euros per month per family. 4 The German Embassy in Moscow, the website of which still has the call not to believe such rumours; and the Chechen refugees, living in Europe, have repeatedly refuted this information.

Despite all this, Chechnya is still a region, from where the flow of refugees to Europe is incessant. 5 According to the Office for Foreigners' Matters, in 2014, only Poland received 3663 refugees from Chechnya, and from January to November 2015 – 2500 refugees. 6

According to official Polish statistics, Chechens are the largest group of asylum-seekers in the country. This is due to the fact that Poland, like other Eastern European countries, is not a desirable destination for asylum-seekers from Syria and other Middle East countries and Africa; and they come here rather seldom. The popularity of the "Polish route" among Chechen refugees is caused by the fact that this is the easiest and most accessible way to enter the European Union from Russia. Despite the ongoing Chechens' inflow, with the start of the migration crisis in Europe, they have ceased to be a large ethnic group of asylum-seekers in Western Europe. Russia, which had until recently occupied the leading place in the list of countries-origins of refugees in the Eurostat statistics, in 2014, went down to the 9th place. Still, in 2014, the number of refugees from Russia exceeded 19,000. 7

Reasons for emigration – persecutions at home and loss of health

The rights defender Svetlana Gannushkina believes that the Chechen residents – asylum-seekers in the countries of European Union, have valid reason for that. In her opinion, the main of them are the fear, which permeated the Chechen society, and the unwillingness to live under the rules prevailing in Chechnya.

"The fact that the majority of Russian citizens, seeking asylum in Europe, are residents of Chechnya is well-known. The reason for people's emigration from there is a constant feeling of fear. The same fear as in 1937 in the Soviet Union," said the rights defender.

Among other reasons, she names corruption. According to her version, in the conditions of high unemployment, to get any middle-paid work, to which there are several competitors, one need to pay a lot of money as bribe.

The Chechen authorities treat differently residents' departure abroad. At the height of the outflow of Chechens in 2013, Kadyrov considered it a normal phenomenon. 8

"I find it absolutely normal that Russians, including Chechens, go to seek for normal life in Europe and in the CIS countries. Migration processes are underway everywhere in the world. Although last year, for example, out of 50,000 Chechens, who came home as guests from abroad, 30,000 decided to stay in the republic."

His statement about the 30,000 Chechens, who decided to stay, is not confirmed by the Rosstat statistics, according to which in 2013 no more than 12,000 people came to Chechnya, while 4700 more than that left the republic.

In 2014, Kadyrov unexpectedly refuted the data about the mass departure of residents of Chechnya, calling it a myth. The head of Chechnya posted a respective statement in his Instagram, saying that "the West is only good for Zakaevs and Udugovs, and it is like a stepmother for an ordinary person."

Ekkehard Maas, a prominent rights defender and the head of the German-Caucasian Society, who helps refugees in Germany, believes that the largest group of asylum-seekers from Chechnya in Germany are the people who had faced the political regime of Ramzan Kadyrov and the Kremlin; relatives of the militants fighting in the armed groupings in Northern Caucasus and Syria, who are persecuted in Chechnya, where a collective responsibility had been declared for terrorism.

At the end of 2014, 15 houses of militants' relatives were burnt down in Chechnya; and relatives themselves were expelled from the republic. The "Caucasian Knot" wrote about it in detail.

Also, according to Mr Maas, many patients with tuberculosis and oncology come from Chechnya, and parents, whose children suffer from cerebral palsy.

According to the 2013 report of the Centre for TB Monitoring of the Russia's Ministry of Public Health, the Chechen Republic is among the regions with the largest count of TB patients per bed at TB hospitals. 9

Among other reasons for Chechens to leave Russia for Germany, Mr Maas cited the deplorable human rights situation; invasion of the authorities into people's privacy; unwillingness of many of them to be part of the system; and a desire to live in better economic conditions.

Way to Europe

Grozny-Moscow-Brest-Terespol... The way of Chechen refugees to Europe starts at the Belarusian Railway Station in Moscow. They come there by train Grozny-Moscow, and then go to Brest. From Brest, they take an electric train to the Polish border checkpoint in the town of Terespol.

Conductors of the express train Moscow-Brest no longer observe the flow of Chechens, as it was two years ago, when they occupied half of the train; but they assert that almost in every train from Moscow to Brest there Chechen families with children.

Amina, a young woman with two children, returns to Lithuania, where her family has an annual residence permit with the right of extension. She visited Chechnya in order to see her relatives. The story of her exile began 7 years ago, when Sulim Yamadaev, the former commander of the "Vostok" (East) battalion, was killed.

"My husband took his service in the 'Vostok' battalion. When the battalion was disbanded, he, as well as many of his colleagues, received various proposals to go to work for Kadyrov's people, but he did not want to work with them, and each time he refused. After the murder of Sulim Yamadaev, several colleagues of my husband, who refused to work for Kadyrov's bodies, were killed; and that was the reason for our escape from Russia."

In 2010, Amina with her husband went to Denmark, where their two children were born; but in spite of this, in 2012, they were rejected the refugee status there and were deported to Moscow. From Moscow, Amina's family went via Belarus to Lithuania, where they were granted asylum, and in a year – also the residence permit.

Amina is dressed in a hijab, which covers also a part of her chin. In Chechnya, this dress style is considered an attribute of Wahhabi followers, whom Ramzan Kadyrov blames as shaitans (devils) and terrorists 10; and following them in Chechnya may end in kidnapping and torture. When asked whether she had problems because of this, and how she felt in Chechnya, she answered that all her stay in Chechnya she was sitting at home.

Prior to her marriage, Amina was a member of a women's dance ensemble; and then she put on her scarf only on the stage. The turning point occurred in Denmark, at the refugee camp. There, she was attending sermons, where it was stated that a woman should most likely be covered; and her husband just welcomed her decision.

"The fact that I'm covered doesn't mean that I'm a fundamentalist," she said. "In Chechnya, there is no freedom of speech, and no justice; people are afraid of telling the truth and declare violations of their rights. I wouldn't like to return to a republic, where I may have problems because of my clothes, and where I can't express my opinion; and if I dare say anything, I may be publicly humiliated, beaten up or killed; but the main reason is in the fact that my husband can't return home. If he does, they'll accuse him of treason and kill him."

Amina is accompanied by her mother-in-law Zarema, who decided to go with her up to Minsk. Until then, she was busy with the children, and joined the conversation, when it came to clothes. Zarema narrated the case with her daughter, who, unlike her daughter-in-law, did not want to wear a headscarf, and even refused to put it on under the demand of her bosses at work.

"My daughter worked as an accountant for the ministry. A few years ago, when all the civil servants were obliged to wear headscarves, she quit her job and went to Moscow, where she immediately found a job with a good salary. She did it because she is very stubborn and does not like, when she is ordered what to do."

The introduction of dress code for women in Chechnya was commented in the report of the Human Right Watch (HRW).

During their stay in refugee camps – from six months to several years, asylum-seekers are not allowed to work and have to live on social benefits. Under these conditions, when the chances of receiving the refugee status and a work permit are small, some of them, who were not in danger in Chechnya, decide to voluntarily return home. These are mainly those, who come for financial reasons, in search of a more favourable economic environment, or for health reasons. According to European laws, immigration services pay for the way home of voluntary returnees. As a rule, after returning home, they continue their previous life.

Thus, a resident of Chechnya named Murad, after waiting for seven months with his family for the refugee status in Germany, voluntarily returned home. The young man came to Germany via Poland in the wake of the mass flow of refugees from Chechnya in 2013. He was using the "Polish route": from Brest to Terespol, and from there in a taxi to Germany.

"We lived not bad; and when I was for the first time denied the status, I filed an appeal. I have small children, and I was afraid that they would grow not like Chechens, and may lose their identity. To be honest, I really missed my parents and was afraid that something may happen to them; and I wouldn't be there. Therefore, I returned," says Murad.

Upon his return, Murad got employed in one of the commercial companies belonging to the leadership of Chechnya. He gets a salary of 15,000 roubles. He says that he sometimes regrets about his return; and the difference between Germany and Chechnya is like heaven and earth.

"Thus, I saw the life in Germany; and I now compare the situation here and there. Maybe it would have been better not to go there. There would have been nothing to compare."

Departure to take treatment, desire to feed family, and earn money for building a house in Chechnya

Not all the Chechen refugees in Europe are people persecuted by the Chechen and Russian authorities. There are those, who leave for economic and health reasons. It is impossible to define the percentage of them. According to rights defenders, the category of persons, who leave Chechnya only for economic reasons, is not defining; there are much more those, who leave because of health problems and prosecution of the authorities.

The reasons for which the Khizir family is leaving are economic. Khizir is 40 years old; in Chechnya he was engaged in construction and repair works. He goes to Poland with his pregnant wife and four children. His financial situation was so bad, says the man, that he was not able to pay for the rented flat in an outskirt of Grozny. Before the New Year, he sold the car for 120,000 roubles; most of this money was spent for the travel. He is going to find some job in Poland; and after gathering enough money for building a house in Chechnya, he plans to return home.

"Europe doesn't interest me as a place of permanent residence, but I can work there as a builder. A friend of mine, who lives there, said that one can earn enough, if working hard. In 4-5 years, I plan to accumulate enough money and definitely return home. I wasn't persecuted, I just want to save money to finish my house and feed my family, as now I physically can't do it in Chechnya: there is no work, but I need to feed, dress and educate my children."

Upon arrival in Brest, at the railway station, Chechen families are met by local "consultants". They can help to rent an apartment, to buy tickets, and organize a Polish taxi to other countries of the European Union.

Malikat, a mother of two children, a native of the Chechen village of Tolstoy-Yurt, already has some experience of crossing the border; she had agreed in advance with Tatiana, a resident of Brest, who bought her train tickets Brest-Terespol and hired a taxi driver to take Malikat from Terespol to Norway, where her husband lives. Should the Poles send the woman back, Tatiana will give her a room in her apartment. The Malikat's "azultrip" began after her marriage in 2009. Her husband, who lives in Norway since 2003, left in order to escape the war; and now he rears three children from his first marriage. He married Malikat, when he came to Chechnya 7 years ago.

In 2009, she went to Norway with her husband, where she asked for asylum. There, their first baby was born. In late 2010, the young mother suspended the consideration of her request for asylum and returned to Chechnya.

"There were family circumstances, for which I had to return," says Malikat. In Chechnya, she gave birth to her second child, and in 2012, she again asked for asylum in Norway; but in February 2015, she was deported along with her two children. "I will try to be allowed to stay with my husband, since children grow up without their father," she says.

Malikat is also wearing a black hijab, covering her chin, which was the reason for her detention by Chechen power agents in central Grozny last summer. "They said that they would check me and let go, but I had to spend six hours at the Leninsky ROVD (District Interior Division), until they checked passports of all the detainees; and then the Imam read a sermon about Wahhabis, although I'm not one of them."

Belarusian border guards do not check the presence of visas, required to enter the EU, in citizens who live in Russia. According to border guards in Brest, at the end of 2015 the number of Russian citizens from the ChechenRepublic, travelling to Poland, reached 200 persons per day. However, as a Belarusian border service officer said in an informal conversation, Chechens are present in almost every Brest-Terespol train. Although Polish border guards return many of them back, they are adamant in their desire to get to Europe.

Most of the refugees are young families with children, childless families are rare, singles are still rarer. Most of those who decide to leave receive a consent and approval of their parents; often parents themselves advise youngsters to leave Chechnya. Now, the split of families is not so painful as before: they are constantly in touch and communicate mainly through the Skype and mobile messagers.

More than a third of passengers in the waiting room for the morning train to Terespol are Chechens. They are about 50-60 for a three-car train. Among them, there are many young men and women, some of them are going for the first time, but the majority are making repeated attempts to move to Poland. Apart of Chechens, there are residents of Georgia. Also, the Chechens, who are already citizens of Poland, are waiting for boarding the train in the waiting room.

Adam is 20 years old; 10 of them he lives in the Polish city of Bialystok. After graduating from college he wants to go to the MilitaryMedicalAcademy and become a military surgeon. In addition to the Chechen and Polish languages, the young man is fluent in Russian and English. He returns from Chechnya, where he went to update his Russian passport. He tells that he felt uncomfortable when in Chechnya.

"The last time I was there, I was 14; then I also went to make my passport. Of course, there are a lot of good things there; most importantly, that the war has stopped, but democracy and freedom are far away. Ordinary people are afraid of the authorities, especially of Kadyrov people; and because of this the youth suffers greatly. A person may be killed for telling the truth; although everyone knows about it, but keeps silent; they may take off your pants for criticizing Putin; they may just kidnap you in the street. Living in the Chechnya, where there are generally no freedom and security guarantees, I wouldn't like; I felt there like a bird, placed into a cage. These people, who travel to Europe with their families, certainly are not running away from good life; there is really some kind of terrible situation in terms of the rule of law and people's rights."

According to Adam, in his city there are many Chechens; young people are mainly engaged in sports; and the main idol of the local youth is the famous Polish fighter Mamed Khalidov.

Past the border – struggle for the right to stay

It takes 20 minutes for the train to reach Terespol. There, people are let out car by car; and refugees are kept in the train until all the passengers with visas go through the passport control. On the platform, the train is surrounded by militaries. Border guards explain such measures by the need to counteract illegal entry into the country. Then, the remaining passengers are taken to a closed waiting hall, where they all will be interviewed, trying to convince the border guards to accept their requests for asylum.

Polish border guards said that the flow of Chechens seeking asylum sometimes exceeds 100 persons a day. One of the officers of the Polish Border Service told in an unofficial conversation that the acceptance of the request for asylum depends on specific cases and on how convincing the arguments about the danger threatening the applicants in their home country are. Not all the Chechen refugees manage to convince border guards to let them into the country; they are sent back to Belarus. However, Chechens take new and new attempts to get into the European Union.

Those, whose requests for asylum are accepted, are sent to a distribution camp, in which they should be kept until the appointment of their first interview with representatives of the Migration Service.

According to the officer, their service has no right to monitor the refugees inside the country.

"If we accept their requests, we give them documents, with which they should go to a distribution camp, but many of them prefer to go, either directly, or after some time, to Germany. We have no right to follow them inside the country, since it is not within the competence of the border service; and there no borders between the EU countries."

As I learnt later, out of my travel companions, they accepted only Malikat's request; and in a taxi, hired by her consultant from Brest, she departed towards Norway. To get there, she has to cross the border of Poland and Sweden. There are no checkpoints in this direction. Khizir with his family was sent back, but on the following day he again attempted to seek asylum in Poland. According to his story, he will try it again and again, as he has nowhere to go back. Later, Khizir's phone was not available, and I could not contact him. Perhaps, he was let into the country, and changed the phone number.

"For 1800 euros I'll bring you to the very Bundestag," says a Polish taxi driver in Terespol to the question about the cost of a trip to Germany. This high cost is only for people without visas, since a person with a visa can fly from Moscow to Berlin for 70 euros. Only those, who can't get a Schengen visa, choose the route across Poland. Speaking about visas, it is worth noting that for natives of Chechnya getting such is virtually impossible without the provision of certificates of the place of work, a stable income, financial well-being, a bank account and other documents, which refugees, as a rule, do not have. By the way, the websites of some of visa agencies directly write that due to a large number of visa refusals, they do not work with the natives of Chechnya, Dagestan and Ingushetia.

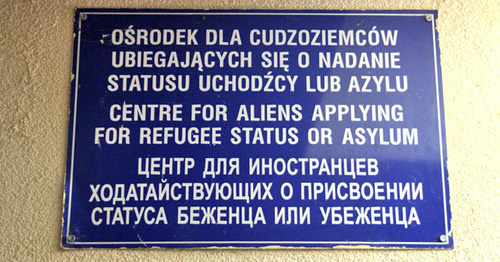

The unremarkable Kozhikov Street in Warsaw is well known to every refugee. Here, there is an office of the Department for Foreigners' Matters, where refugees come to get interviewed, for documents and other matters. Here, there is also an office of a major local non-profit organization for helping refugees "Salvation" (Fundacja Ocalenie), in which, inter alia, Chechens, recent former asylum-seekers are working.

According to their stories, Polish authorities are more inclined to give, rather than the refugee status, the so-called "tolerated stay" status. According to this status, a refugee has the right to live in Poland for one year, enjoy the social benefits at his/her residence, and to work. The majority of Chechens coming to the country prefer to move further to Western Europe – mostly to Germany.

Other most popular countries are Austria, Belgium and Denmark. In accordance with the Dublin III Regulation of the European Union 11, the responsibility for considering a request for asylum is on the first country of the European Union, entered by an asylum-seeker. For those Chechens, who leave Poland for other EU countries, it means that they will be returned to Poland. This procedure can take from six months to several years. During this time refugees live in camps for asylum-seekers.

Chechen refugees are very suspicious to those who are interested in their lives. Rumours are circulated here about "agents", sent by Chechen authorities to spy on them and reveal "enemies". European Chechens became especially cautious after the murder in Vienna of Umar Israilov, a refugee and a former bodyguard of Ramzan Kadyrov, who had talked about private prisons in Chechnya, where people disliked by the authorities are tortured. The Austrian Prosecutor's Office had charged Lecha Bogatyryov, an employee of the Chechen Ministry of Internal Affairs (MIA), of killing Israilov.

On January 13, 2009, inVienna, Umar Israilov, 27, a former bodyguard of the head of Chechnya Ramzan Kadyrov, was shot dead; he was living in exile and evidenced against the Chechen leader at the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). Ali (Sharpudi) Israilov, Umar's father, told the "Caucasian Knot": "The methods of these lowlifes are well-known to us: they act in the same way as they acted against my son, that is: they bribe people, force them to kill dissenters and blame performers for that, while remaining in the shadow. But we all know, and the whole world knows about it; that without funding by them, without their team, and without their knowledge such things never happen."

The recent statements by Kadyrov on the responsibility of relatives living in Chechnya for militants' words and actions, according to refugees, are treated in Europe as an additional reason for European Chechens to be careful in their statements, since most of them have close relatives living in Chechnya.

Women – for their husbands

About 150 persons live in the centre for asylum-seekers Targovek, located near Warsaw. This centre is for women only. Most of its residents are Chechen women with children; refugees from Ingushetia and Dagestan also live here.

Luiza came in 2012. From Poland, she immediately went to Germany to her husband, who a year earlier had fled from power agents' persecution, who accused him of having links with a murdered militant. Luiza left Chechnya because of pressure by power agents, which continued after her husband's fleeing.

"In 2009, power agents killed a school friend of my husband. One day before the murder, he was our guest; we lived in the Staropromyslovskiy District of Grozny. Law enforcers said later that he had been a Wahhabi and fought for the militants. After his murder, they arrested my husband's brother, saying that he was involved in the affairs of the murdered friend. We had to pay a million roubles for his release. After his release, the pressure of militaries has not stopped – my husband and his brother were often summoned to the police. In 2010, they left for Germany. After that, I was often visited by the district policemen and other militaries, who demanded from me to return my husband and his brother, saying that the police had questions for them, etc. In 2012, I was forced to close my shop in Grozny and leave. I came to Germany via Poland, but six months later I was deported back to Poland, because they had my fingerprints there. In autumn of 2013, I again went to Germany and lived with my husband in Bavaria, where our child was born. However, last summer I was again deported to Poland; and now I live here. The conditions in Germany, of course, are much better; therefore, everyone wants to get there. I would love to go back home and live next to my mother in a full-fledged family, but now I can't go back home for security reasons."

Currently, Luiza attends courses of Polish and dreams about reunification of her family.

The women with similar stories, whose husbands were persecuted in Chechnya, are in majority here. Basically, they are widows of killed members of illegal armed formations (IAFs) and their relatives; there are divorced women, who were threatened to take away their children at home, as well as those who have parted with their husbands already here, in Europe.

In 2013, the 42-year-old Taisa with her three children arrived in Poland from the Nadterechny District of Chechnya. Her husband took part in the war against Russian troops during the Chechen Wars. In 2007, after militants announced the creation of "Imarat Kavkaz" (a terrorist organization banned in Russia), Taisa finally lost contact with him; but from time to time, as she said, power agents demanded from her to give them information about the whereabouts of her husband, threatening to take away their children and put her to jail for sheltering a terrorist. In December 2013, in the wake of the flow of refugees, she came first in Poland, and then to Germany. However, six months later she was also sent back to the first host country. Nevertheless, Taisa is not going to stay in Poland and is preparing to go to Germany again, upon expiry of six months, and ask for asylum again.

Women in Targovek told me about a small Chechen cafe in the outskirt of Warsaw. The facade of a small premise attracts by colours of the flag of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria. The chief cook in the cafe is Yisita Vitaeva, helped by her youngest son Ibragim. The boy has his left arm paralyzed; he recently began suffering from intensive cramps; therefore, he needs permanent medical supervision.

He received his trauma during an attack of armed grouping on the Vitaev family in 2003. "They ordered us to be quiet, but the child began crying; and then one of the attackers hit him with the butt on his head. He fell on his left arm; and it is paralyzed since then. Two years ago, his cramps intensified; and since medicine in Chechnya is very weak, we arrived here in the hope of finding medical care for my son," said Yisita.

The cafe, where we are, was opened two months ago by Yisita's eldest son. She sent him here as early as 2011, when the organizer of the attack on their house was released after 7.5 years in prison, and began threatening her.

"When he came out of prison, he began saying that he had been imprisoned for no guilt and would certainly avenge us for his years spent in prison. Then, I immediately decided to send my eldest son outside Chechnya. I lost two children during the war; and my heart won't survive more casualties," says Yisita.

Umar, the Yisita's eldest son, is the owner of the cafe. Upon his arrival in 2011, having lived in Poland for six months, he moved to Sweden, and a year later arrived in Norway, where he organized a small business of selling sandwiches. During his wanderings, he learned the Polish, Norwegian, Swedish and English languages.

In 2013, Umar was sent back to Poland. Here, for the money earned in Norway he bought a few acres of land and arranged a cafe there, which is documented to the name of his acquaintances. Now, he is preparing to open the second eatery. For two years, Umar was in hiding, without any permits and documents on his stay in Poland.

The Migration Service offered him to bring his application, and gave him a permission to stay. Next year, he hopes to obtain a residence permit.

According to Luiza Adaeva, the head of the Chechen Cultural Association "Sintar", who is living in Poland since the 1990s, now there is no organized Chechen Diaspora in Poland. She attributes this situation to the fact that there are very few people left here, who came here in the 1990s; and those who are coming now seek to go further to the west. Chechens as a nation are treated very warmly by Poles. At the time, Warsaw held rallies against the war in Chechnya; and various programmes were initiated to help Chechnya residents. From 1997 to 2007, the "Chechen Centre" was functioning in the centre of Warsaw, established as a representative office of the independent ChechenRepublic of Ichkeria.

Last autumn, over 2500 residents of Poland signed a petition against deportation of the Chechen Khuchbarov family to Russia. The court reversed the decision of the Migration Service and allowed the family to stay in the country.

To the question of how they treat the flow of refugees in Poland, Elsi Adaev, who is studying international relations at the University of Krakow, says that supporters of accepting refugees give an example of Chechens as an ethnic group of Muslims, who live an integrated life within the Polish society.

"Now, we are given as an example. When they hold discussions among supporters and opponents of adoption of refugees, the former give us as an example, as people well-integrated into the society and engaged in different spheres of activity. The point is that many are now sceptical about Muslims' inflow from the Middle East, since they fear that they will set their own rules here," said Elsi Adaev.

Nevertheless, we cannot say that Poland is a country where Chechens are deeper than in other countries integrated into the local society. According to Elsi Adaev, supporters of accepting refugees appeal to the experience of accepting Chechen refugees, tens of thousands of whom Poland has accepted.

Thus, advocates of accepting refugees want to convince their opponents that there is no threat to local population from Muslim refugees from Syria and other countries. We must understand that in Eastern Europe many people poorly know Muslims and Islam, which is sooner associated in them with something dangerous and alien.

The acceptance of a request for the refugee status does not mean granting the status. According to its European commitments, Poland is obliged to consider requests for asylum, but the consideration process takes at least six months; and during this time many applicants go further.

According to the European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE), in 2011, the countries of European Union gave shelter to about 100,000 Chechen refugees. 12 According to the Chechens, who are living not for the first year here, there are now some 12-20,000 people from Chechnya in Poland.

From Poland to Germany

The office of the German-Caucasian Society (Deutsch-Kaukasische Gesellschaft) is a meeting place for Berlin Chechens. It hosts cultural events of Caucasian nations; meetings of compatriots; every day, dozens of Chechen refugees come here for help with their "azultrip" problems.

Ekkehard Maas, the head of the Society, said that now there are several groups of Chechens in Berlin. These are Soviet intellectuals, people devoted to Ichkeria, religious people, the youth focused on sports, and others.

According to his story, at least 15,000 Chechens live here; no more than two thousand of them have citizenship; many have stay and residence permits. 13

With regard to the 13,000 people, who came in 2013, some of them under the Dublin III Regulation were sent back to Poland; others are still waiting for decisions on their requests for asylum; and only about a hundred were granted residence permits. There are also those, who suspended processing of their requests for asylum and voluntarily returned to Chechnya 14; newcomers are sent to distribution camps, where they are waiting for consideration of their cases.

People in Germany also fear Kadyrov's statements about the collective responsibility of family members for statements of their relatives, living in Europe. It is obvious that they are afraid of saying too much, even in private conversation without a voice recorder, which is confirmed by my interlocutor, who had served as minister in the government of Ichkeria, and who lives for 10 years in Berlin.

"People fear not for themselves, but for the relatives in Chechnya, for whom our words may be a real problem. We're strongly shackled with this collective responsibility, because everyone has a hundred close relatives in Chechnya," he said.

Many keep silent and off the politics, not to lose the opportunity from time to time to visit Chechnya. It should be noted that in summer in Chechen streets there are many cars with European number plates; in rural streets one can meet children, who speak foreign languages better than the Chechen language. These are European Chechens, who come to Chechnya on vacation.

According to the Society of German-Caucasian Friendship, over 7000 natives from Chechnya live in Berlin; and overall, over 150,000 are scattered over Europe. 15 The largest Diasporas are in Austria, Belgium, Germany, Norway, France, Denmark, Poland and Sweden.

Most of the Chechens, now living in Germany, have the Duldung status (the patience-to-stay status), which may last up to 10 years, until the immigration authorities take a final decision either on deportation, or granting the refugee status.

A resident of Grozny, Rukman by name, sought to obtain a Schengen visa for almost a year. For the first time he was denied a tourist visa; and to make it, he gave 30,000 roubles to intermediaries. At the end of 2015, he managed to receive a short-term tourist visa, under which he flew to Europe (at his request, we do not name his city of residence). Rukman associates the reasons, for which he was forced to leave Chechnya, with his professional activities; he is engaged in programming.

"There were many reasons for leaving the homeland, but the main reason was in the increased unhealthy interest of power agents in the life and activities of free-thinking citizens in our republic. My story is related to the persecution of me in connection with my professional activities, indirectly related to politics; in particular, with a forced inability to work on my projects," said Rukman.

According to his story, most people leave Chechnya because of repressions for their dissent, and social injustice.

"We have a tsar there, who decides whom to execute and whom to pardon; the freedom of speech is out of question. Any dissent, including on the Internet and in conversations, is brutally suppressed. And people are running away, I think, also because Chechens, despite the heavy losses of recent decades, are primarily freedom-loving people, who find it difficult to put up with the situation, where there is one group, for which everything is allowed, and all the rest who are serving this group."

As to the religious matters, the young man sees some progress, although there are problems here too.

"In terms of the religious freedom, there has been a significant progress, thanks to thousands of people, who brought the ultimate sacrifice during the past wars; however, there are unspoken rules here, which undergo changes, depending on the moods of the regime. One day, for wearing a beard, the police may detain you and expose to beatings and humiliation; on the other day, a beard is permitted and approved, like throughout the Muslim world. However, this state of things can sooner provoke neurosis in a normal person than a feeling of religious freedom and prosperity. Not to mention the 'attributes' of the so-called Wahhabism, like shortening of trousers, denial of poetry performances during celebration of birthdays, and so on. However, here, as well, there is this neurotic component, when Kadyrov receives orders from the King of Saudi Arabia, the main Wahhabi, but local followers of this trend may face execution only."

Rukman prefers not to tell about his life in the new country, saying only that he was waiting for the decision of migration authorities on his application for asylum. Rukman explains the reluctance of refugees to talk about their life by the existing threats to their relatives in Russia.

"It was because of threats to relatives that the largest Chechen Internet portals were closed, namely: the teptar.com, adamalla.com and others; persecutions are carried out, and threats are posted in social networks. Many fear because Chechens have strongly developed family ties; and it turns out that all the relatives living in Russia, are hostages of the totalitarian regime."

Deportation from Europe and fate at home

At the end of February of 2016, three children of Nebila Borzaeva, a native of the ChechenRepublic, who had asked for asylum for her family in Switzerland in January, were deported from Switzerland to Russia. Magomed, Rasul and Aminat, whom the Swiss authorities deported without the document (certificate of return), mandatory in this case, were kept for three days by Russian border guards in the transit zone of the Domodedovo Airport. According to Nebila's son, the children were kept in a closed, dirty room, with no normal conditions for living. 16

On March 2, 2016, three children of Nebila Borzaeva were released from the transit zone of the airport and handed over to her relatives.

Nebila herself with her youngest child is in the mental hospital in Zurich; however, she and her 10-year-old son are kept in different hospitals of the city.

On February 27, 2016, a special flight from Germany to Grozny brought the family of Maryam Gonchaeva, a native of Chechnya, who is seriously ill. She had sought, with her husband and children, for refuge in Germany three years ago in the context with her severe oncology disease, hoping to get medical treatment there. In early February, German doctors pronounced their impotence before the Maryam's progressive disease, making a forecast on a short duration of her remaining life. Then, Maryam turned, through the WhatsApp, to Ramzan Kadyrov asking to help her to return home. "I had come here hoping to find a treatment for my illness. Now, I have less than two months left. Please give me a chance to die in my homeland," she said in her appeal. On March 10, the woman died.

The "Caucasian Knot" cannot keep track of their further fate, but we know fates of other refugees, who were deported to Russia.

During 2015, we know four cases: murders and kidnappings in Russia of the natives of Chechnya, who had been deported to the country after refusals of granting the asylum.

In February 2015, after being detained by power agents, Kan Afanasiev, a resident of the Nadterechniy District of Chechnya, was killed; a few months earlier, he was deported to Russia from Sweden. Last July, Zaurbek Zhamaldaev, a native of Chechnya, disappeared in Moscow; in 2013, after denying the refuge, he was deported from Poland to Russia. His friends reported that he had been shadowed before his disappearance. The fate of the man is still unknown.

According to Aage Borchgrevink, an adviser to the Norwegian Helsinki Committee, in Chechnya, where the whole society is permeated with fear and distrust, it is difficult to encourage people to tell about their relatives or friends, who have been exposed to abuse, or who had contact with the movement of resistance. Those who dare speaking are putting themselves and their families at risk of repressions.

Øystein Vinstad, a journalist from Norway, who was beaten up, among others, on March 9, 2016, had conducted an investigation into the murder of Umar Belimkhanov and Apti Nazhuev, residents of Chechnya, who were killed after returning to Chechnya from Norway.

Umar Belimkhanov, a native of the village of Tsentaroy of the ChechenRepublic, was found dead in January 2013. According to Lene Witteland, the director of the section of Eurasia and Russia of the Norwegian Helsinki Committee in Oslo, Belimkhanov had requested asylum in Norway, but, despite the warnings of rights defenders about threats to him in Russia, received a refusal and was sent to Russia in November 2011. Upon his return to Chechnya, he was arrested for a few weeks. In his letter, sent to employees of the Human Rights Centre (HRC) "Memorial" in May 2012, he wrote that he was tortured during his arrest.

"He wrote that during interrogations he was reproached for having left the republic; they threatened him that he should not think of trying again to leave the territory of the republic, and threw him in his face the documents about the murder of his brother, published by organizations for the protection of human rights, and his interview to Norwegian mass media about human rights violations in Chechnya, which he witnessed at home. At the end of December 2011, he was released, but he feared for consequences for his family in case of his repeated departure," Lene Witteland told the journalist of the "Caucasian Knot".

In December 2015, the "Ny tid" (New Time) published the investigation by Øystein Vindstad about what happened to the two Chechens, who had been deported from Norway to Russia. The publication, which according to Aage Borchgrevink, was read by the whole of Norway, was posted under the heading "Tortured and Killed". 17

The two Chechens, about whom Vindstad had written, came to Norway in 2008, but they were refused the refugee status. The Norwegian Helsinki Committee and the HRC "Memorial" tried to stand up for the immigrants, insisting that the stay in Russia would be dangerous for both of them. However, the men were forced to return to Chechnya in late 2011.

Belimkhanov was found dead on December 26, 2012. According to official reports, he died in a car accident; the exact circumstances of his death were never cleared out; numerous signs of torture were found on his body; while the car, involved in the accident, had no scratches, said the advocate Brynjulf Risnes, who defended Belimkhanov's interests before the Norwegian migration authorities.

"As far as we know, the family was refused of conducting a forensic medical examination. We believe that his death was caused by torturing and abusing him," said the advocate.

Apti Nazhuev, who was seeking asylum in Norway, was deported in 2011; after living for a month in Moscow, he returned to Chechnya with his family. On May 18, 2013, he was kidnapped by armed men. On June 10, his body was found in the Argun River. According to Lene Witteland, who advised Nazhuev on obtaining asylum in Oslo, signs of torture and numerous cuts were found on his body.

- "Azultrip" (travel with the aim of obtaining the asylum right) is a slang expression, widespread among refugees. From the Polish / German "azyl / asyl" (asylum) and English "trip" (travel).

- Napływ cudzoziemców ubiegających się o objęcie ochroną międzynarodową do Polski w latach 2009-2015.

- "This is a historical record, in which about 83% are Russian citizens of Chechen nationality," said Rafal Rogala, the head of the Department for Foreigners' Matters: NewsBalt, 25.10.2013; Russia Daily: Why Are 1,000s of Chechens Seeking Asylum In Berlin? // EA Worldview, 12.01.2014.

- Welcome Money? Rumour Lures Chechen Refugees to Germany //Spiegel, 18.07.2013.

- Williams L., Aktoprak S. Migration between Russia

and the European Union: Policy implications from a small-scale study of irregular migrants. International Organization for Migration. Moscow, 2010. P. 17-18; Asylum Levels and Trends in Industrialized Countries – 2011. Statistical overview of asylum applications lodged in Europe and selected non-European countries. UNHCR. Geneva, 2012. P. 15, 22-24, 32. - Polska przyjęła już ponad 80 tysięcy Czeczenów i wciąż przyjmuje następnych. Czy komuś to przeszkadza? // Natemat, 21.09.2015.

- According to Eurostat: in 2013: 41,000 from Russia, 10%: Asylum in the EU28 // Eurostat, 24.03.2014; in 2014: 19,700 from Russia: Asylum applicants and first instance decisions on asylum applications: 2014 // Eurostat, 13.03.2015.

- R. Kadyrov. Many Chechens return to their homeland // Official portal of the head and the government of the Chechen Republic, 27.05.2013.

- Situation with Tuberculosis and Work of Anti-Tuberculosis Service of the Russian Federation in 2012 // Federal Research Institute for Health Organization and Informatics of the Russia's Ministry of Public Health, p. 4, 6, 8.

- kadyrov_95 // Instagram

- Dublin III Regulation – The legislation of the European Union defining the liability of EU member-countries for consideration of applications of asylum-seekers in accordance with the Geneva Convention on the Status of Refugees (1951) and the European Directive on Conditions for Asylum (2011). Dublin III Regulation was adopted in 2013, replacing the Dublin II Regulation (2003) and the Dublin Convention. The Dublin Convention was adopted on July 15, 1990, and entered into force on September 1, 1997, for the signatory countries thereof (Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and United Kingdom). On October 1, 1997, Austria and Sweden acceded to it; on January 1, 1998, Finland did it. In 2001, a similar agreement was signed with Norway and Iceland: Dublin Regulation // European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE); Agreement between the European Community and the Republic of Iceland and the Kingdom of Norway concerning the criteria and mechanisms for establishing the State responsible for examining a request for asylum lodged in a Member State or in Iceland or Norway // European Council, 19.01.2001.

- ECRE Guidelines on the Treatment of Chechen Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs), Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Europe, Brussels, 2011. P. 13.

- According to the Jamestown Foundation, as of 2013, there were 12,000 Chechens in Germany: Continuing Human Rights Abuses Force Chechens to Flee to Europe // The Jamestown Foundation, 07.03.2013.

- In summer of 2015, certain countries of Europe resumed a programme of the IOM (International Organization for Migration) aimed to help in voluntary return and reintegration. The refugees who are voluntarily returning to their homeland receive up to 3500 euros for personal needs. 60% of those who return to Chechnya invest this money into agricultural activities: Assisted Voluntary Return and Reintegration (AVRR) for returnees to Afghanistan, Pakistan and the Chechen Republic of the Russian Federation:

Project ending and restarting // International Organization for Migration (IOM), No. 19, July 2015; Difficult decisions. A review of UNHCR's engagement with

Assisted Voluntary Return Programmes. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Policy Development and Evaluation Service (PDES). Geneva, 2013. P.16. - The European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE) gives, as of 2011, the figure of 100,000 Chechen refugees: ECRE Guidelines on the Treatment of Chechen Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs), Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Europe…, P. 13.

- "We are kept in some closed dirty premise, which has no beds and no other conveniences. They give us foodstuffs with expired shelf life twice a day. The only furniture they have here are a couple of chairs, on which you can have a short nap," Nebila's son told the "Caucasian Knot" correspondent by phone.

- Torturert og drept etter å ha blitt nektet asyl i Norge // Ny Tid, 17.12.2015.